How California farms can reduce pumping power costs

Irrigation pumping costs can vary widely depending on field size, system pressure, pump efficiency and utility rate structure.

Photo/Courtesy of Rain Bird

By Charles Burt

The cost of electrical power can be a large component of an annual farming budget in California—for all irrigation methods. Here are some notes on how various farms deal with the increased costs.

AG Electric Pumping Rates.

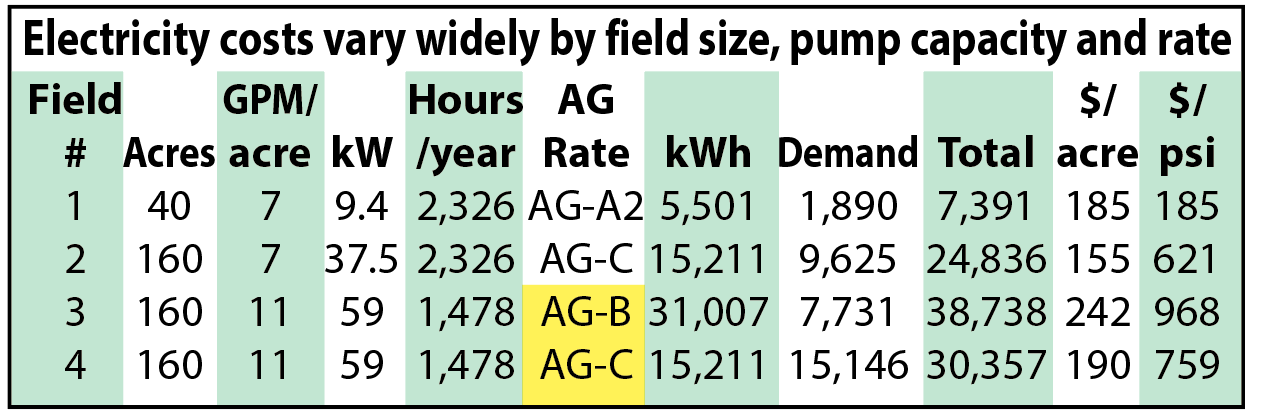

The table below provides annual power cost estimates for three hypothetical fields. Each has the same annual pumped volume per acre (3 acre-feet) and pressure (40 pounds per square inch, or about 92 feet) and pump/motor efficiency (52%). The differences are the size of the fields (No. 1 with 40 acres, No. 2 with 160 acres), the size of the pumps (No. 2 at 7 gallons per minute per acre and No. 3 at 11 gpm per acre), and for field No. 3 a Pacific Gas & Electric Co. AG-C rate versus the default PG&E AG-B rate.

The table below provides annual power cost estimates for three hypothetical fields. Each has the same annual pumped volume per acre (3 acre-feet) and pressure (40 pounds per square inch, or about 92 feet) and pump/motor efficiency (52%). The differences are the size of the fields (No. 1 with 40 acres, No. 2 with 160 acres), the size of the pumps (No. 2 at 7 gallons per minute per acre and No. 3 at 11 gpm per acre), and for field No. 3 a Pacific Gas & Electric Co. AG-C rate versus the default PG&E AG-B rate.

The table above shows that the difference in both the cost per acre and cost per psi can be substantial. Work closely with your utility agricultural representative to explore different rate options with your specific numbers.

Improve the pumping plant efficiency. This may be as simple as replacing a pump. A pump may potentially be very efficient—but not with your flow rate and pressure combination. Low pump efficiencies also occur because of worn bearings, worn impellers and bowls or a change in pressure or flow conditions over time.

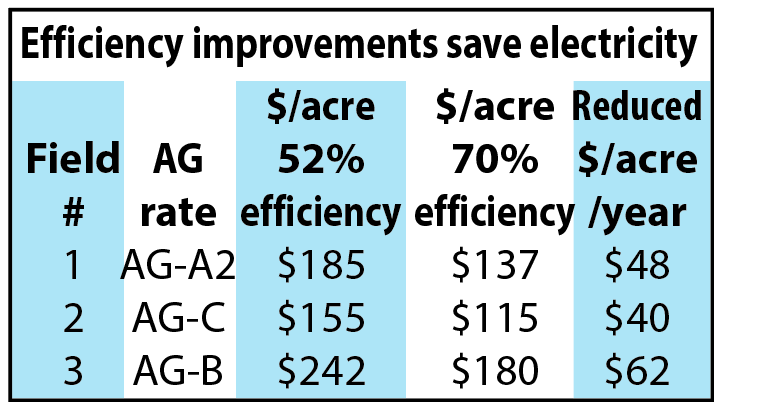

The table below continues with the same three fields as the earlier table and illustrates the cost impacts of improving the pump/motor system efficiency.

Lower the total pressure requirement. For a well, this usually means properly cleaning it to reduce the drawdown, using hydrojetting, plus following up with a chemical treatment. Overpumping to “develop” a well is much less effective. A secondary benefit of well screen cleaning can be a reduction in sand pumping, which extends the life of bowls and impellers. Less drawdown will mean more flow rate for a well with an open discharge. Therefore, unless you change pumps, reduce the pump speed or hours of operation. You may pay the same for power but less per acre-foot pumped.

For a new drip irrigation system of moderate size, the standard 40-45 psi pump discharge on a flat field can usually be dropped to about 25 psi with proper selection of valves, emitters, filters and hoses/pipes. Some excellent irrigation dealerships are very successful with this. The advice is to purchase a well-designed system as opposed to just receiving an assembled material list. The electricity bill savings are proportional: The power cost for a 25 psi booster (same flow rate) should be about 55% of the power of a 45 psi booster pump.

With an existing drip or sprinkler system, reducing the pressure requirement—for example, changing valves to ones that have less pressure drop—may not reduce your pumping bill. This is because if the flow rate stays the same, the old pump will still deliver the same pressure—and use the same kilowatt—with the excess pressure being burned up in some other valve, pressure regulator or pressure-compensating feature. Again, pumps need to match the system to achieve maximum efficiency and savings from lower pressure requirements.

Variable frequency drive, or VFD, panels are quite popular and often have major operation advantages. For example, if the pump is oversized, the VFD can be used to lower the pump pressure and reduce the pump kilowatt. But they do add an additional component of electrical system inefficiency. When you purchase one, obtain a written guarantee that the total packaged VFD system efficiency—from input to enclosure to output terminals—shall be no less than 94% at full-load conditions, including all ancillary components such as reactors, filters and surge suppression, based on integrated package testing by the manufacturer or a certified integrator.

If you are using only a VFD for a slow startup, check with your electrician or VFD supplier to automatically switch the operation to across the line once the pump reaches full speed.

Reduce the demand charge. Lowering the pressure requirement by 20% reduces the demand charge—and kilowatt hours—by 20%, assuming a pump matches the new conditions.

Improve irrigation efficiency. By itself, this may not reduce the power bill if you are already under-irrigating. But improving the irrigation distribution uniformity, or DU, eliminating the irrigation of dead trees/spots and good irrigation timing can contribute to a better yield or crop quality for the same applied volume of water and same power bill.

A cautionary note about reducing pressures. For an existing drip or sprinkler system, do not reduce the pump pressure to the point where you decrease the uniformity of water distribution throughout the field. Pressure-compensating emitters lose their pressure-compensating ability at some minimum pressure—and there is no industry standard for this. Some pressure-compensating microsprinklers have no pressure-compensating ability below 20-25 psi. Larger field crop sprinklers need higher pressures than smaller sprinklers to obtain a good overlap pattern and to create small water droplets that do not seal the soil surface, thereby having less runoff compared to larger droplets. Low pressure sprinkler nozzles might provide a reasonable overlap pattern at a lower pressure but usually have large water droplets that can seal the soil surface and cause runoff problems on California soils.

Charles Burt is professor emeritus of irrigation and founder of the Irrigation Training and Research Center at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo. He can be reached at charlesmburt@gmail.com.

The latest news from AgAlert.com

- Grape glut lessens as growers scrap vines

- Bill brings back ag overtime tax credit proposal

- Solving veterinary shortage is crucial for agriculture

- From the Fields: Laura Gutile, Madera County pistachio grower

- From the Fields: Jennifer Beretta, Sonoma County dairy farmer

- From the Fields: Frank Hilliker, San Diego County egg producer

- From the Fields: Bruce Fry, San Joaquin County winegrape grower

- 'Unrelenting' fog aids Central Valley fruits and nuts

- Strong beef prices keep milk replacement heifer count low

- Transplant nurseries celebrate seed improvements

- Advocacy in Action: Tricolored blackbird, government shutdown, farm bill, fumigation alternatives, air board workshop

- How California farms can reduce pumping power costs

- Award applicants sought for Leopold Conservation

- Section 179 deductions for farm machinery in 2026