In rural districts, backlash mounts against Prop. 50

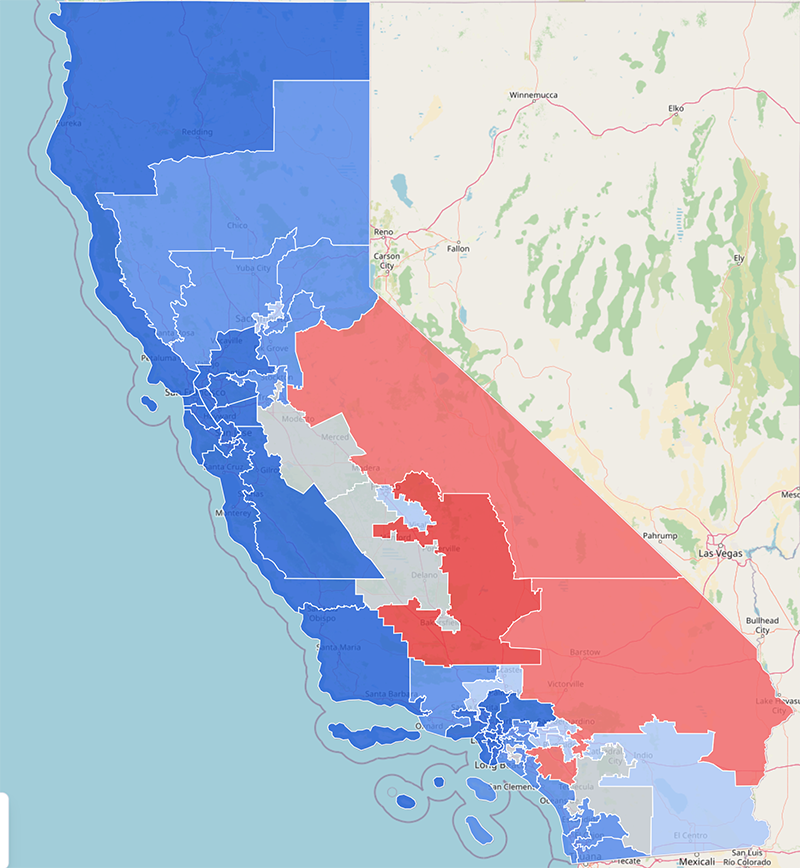

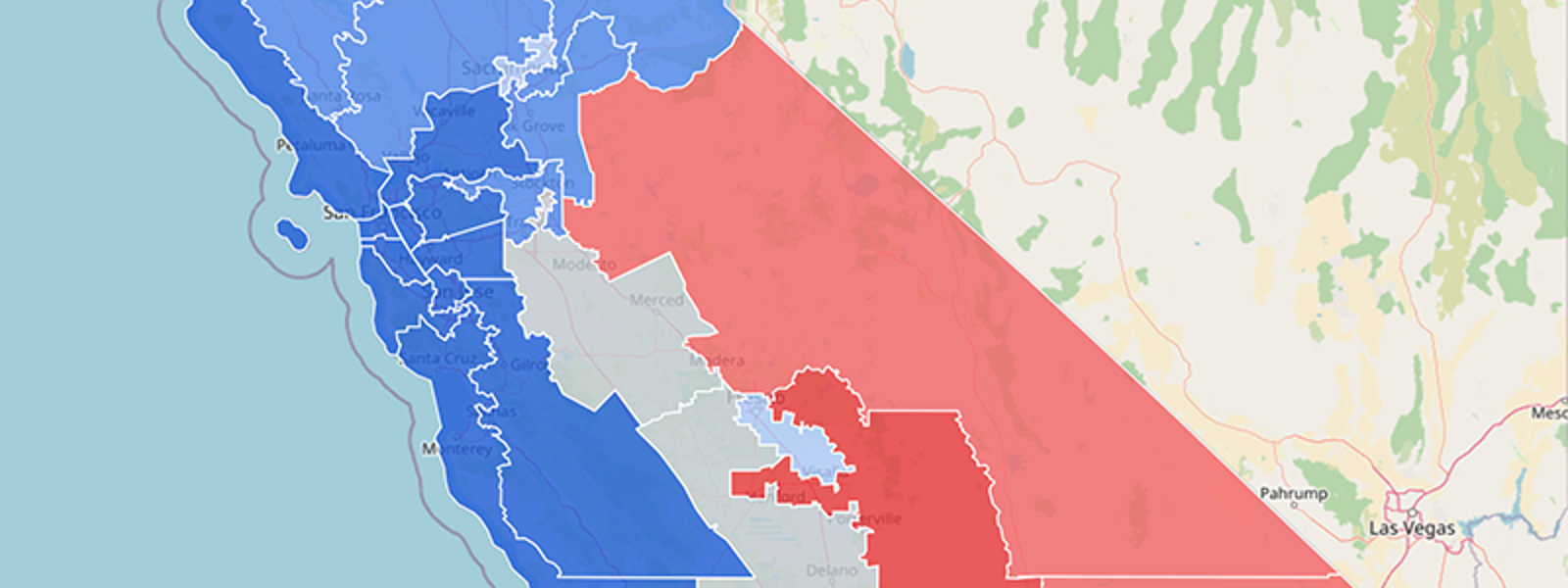

Proposed map under Prop. 50.

Map/redistricting.optiqdata.com

By Caleb Hampton

With Californians beginning this week to cast their votes on Proposition 50, groups representing rural constituents are pushing back against the ballot measure, which would allow the state Legislature to draw new congressional maps ahead of next year’s midterm elections.

Proposition 50 was crafted this year by California Democrats—and championed by Gov. Gavin Newsom—in response to President Donald Trump urging Texas and other Republican-controlled states to redraw their congressional maps to engineer new districts that would likely deliver more Republicans to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Experts project Texas’ redistricting plan will flip five Democrat-held seats, while California’s plan—if Proposition 50 were to pass—could flip five seats that are held by Republicans.

Because a nonpartisan, independent redistricting process is enshrined in California’s state constitution, the state must get permission from voters before handing map-drawing power to the Democrat-controlled state Legislature.

Under Proposition 50, California’s redistricting process would revert to an independent commission after 2030.

The proposed map, which was drawn in secret, aims to benefit Democrats largely by breaking up several of California’s rural districts and attaching the splintered voting blocks to urban-dominated districts.

It would dismantle District 1, which encompasses a large swath of rural, northeastern California, dividing the region into three districts. One of the proposed districts would lump Modoc County with Sausalito, even though the former is closer to Idaho—two states away—than to the Golden Gate Bridge.

Much of the rural, Republican-leaning Central Valley would also be carved up.

Lodi, the top winegrape-producing region in the nation, would be divided into three separate districts. Coalinga, a cattle ranching hub, population 16,722, would be appended to a district that includes San Jose, population 997,368.

As the Nov. 4 special election approaches, advocates for rural communities and interests have increasingly spoken out against the ballot measure.

Supervisors in counties such as Siskiyou, Shasta and Kern have voted to formally oppose it, as has the Lodi City Council.

Last month, the California Farm Bureau, which represents more than 26,000 farmers and ranchers, launched a campaign opposing Proposition 50.

“Urban populations already have the loudest voice and the most representation in California politics, while rural communities struggle to be heard on important issues such as land use, labor regulations and environmental rules,” California Farm Bureau President Shannon Douglass said. “This measure worsens that imbalance.”

Douglass called on the organization’s membership to reject the proposition.

“All Californians deserve equal representation,” she said. “That includes people in rural communities.”

Clark Becker, a Butte County rice and prune grower, said he was heartened by the Farm Bureau’s campaign.

“This is somewhat of a last stand, in my opinion, when it comes to representation,” said Becker, who serves on the California Farm Bureau board of directors. “This will affect our membership.”

Becker is represented in Congress by Rep. Doug LaMalfa, R-Richvale, who is a fellow rice farmer.

“It’s a big deal,” Becker said of being represented by a local farmer.

He said he valued LaMalfa’s position on environmental regulations and his response to disasters Butte County residents have faced in recent years, including the Camp Fire that destroyed much of the town of Paradise in 2018.

“It’s very important to have a representative who doesn’t just show up when there’s a disaster, but who is there every day—that you can interact with and get ahold of,” Becker said, adding that he has run into LaMalfa at county Farm Bureau meetings and rice processing facilities. “It’s easier to hold someone accountable when they’re part of your community.”

Should Proposition 50 pass, LaMalfa’s district would be broken up, with Butte County included in a new district stretching toward the coast to encompass more populated, Democrat-leaning regions such as part of Sonoma County.

Becker said he worries that a representative from an urban area, however well intentioned, “won’t even know what they’re representing” when it comes to farming communities.

“It’s important that our representatives live in rural California and understand the struggles that we have,” he said.

Steven Fenaroli, a policy advocacy director for the California Farm Bureau, cautioned that California’s tit-for-tat gerrymandering move could undo decades of work that helped the state establish itself as a model of good governance.

“Two wrongs don’t make a right,” Fenaroli said, referring to Proposition 50 proponents’ rationale of countering Texas’ redistricting.

In 2008, Californians voted to establish the state’s independent Citizens Redistricting Commission, a 14-member panel that uses a public process to draw new congressional districts every 10 years.

The process, which involves hundreds of meetings and a public comment period, stipulates that “communities of interest,” or people who share common cultures, ways of life or other traits, be grouped together in congressional districts.

“We should do what we can to protect the work the commission did,” Fenaroli said.

Douglass, the Farm Bureau president, warned that although Proposition 50 only temporarily allows partisan redistricting, cracking open the door to gerrymandering in California could have lasting consequences.

“This ballot measure sets a dangerous precedent,” Douglass said, adding that it could lay the groundwork for permanently eliminating the state’s independent redistricting commission. If Proposition 50 passes, she said, “there is no telling what may come next.”

The Farm Bureau president emphasized that the organization was not taking a partisan stance but standing on principle.

In 2010, Farm Bureau opposed Proposition 27, which would have permanently disbanded the state’s independent redistricting commission. The same year, the organization endorsed Proposition 20, which authorized the commission to draw California’s congressional districts.

“We have been a proponent of the independent process for a long time,” Douglass said.

California farmers and ranchers are the backbone of a $61 billion agriculture industry, producing much of the nation’s fruits, nuts, vegetables and dairy products.

“Representation is really key to helping us do that,” Douglass said, adding that the sector faces major challenges. “Now is not the time to weaken our ability to advocate for policy solutions.”

Caleb Hampton is assistant editor of Ag Alert. He can be reached at champton@cfbf.com.

See related news stories...

• Oppose Prop 50 - Join the Coalition Today

• Inside Farm Bureau: Why farmers and ranchers must reject Proposition 50

• Sacramento Bee opinion: Liberals and conservatives are familiar foes of California gerrymandering