Farmers plant less cotton in face of stagnant market

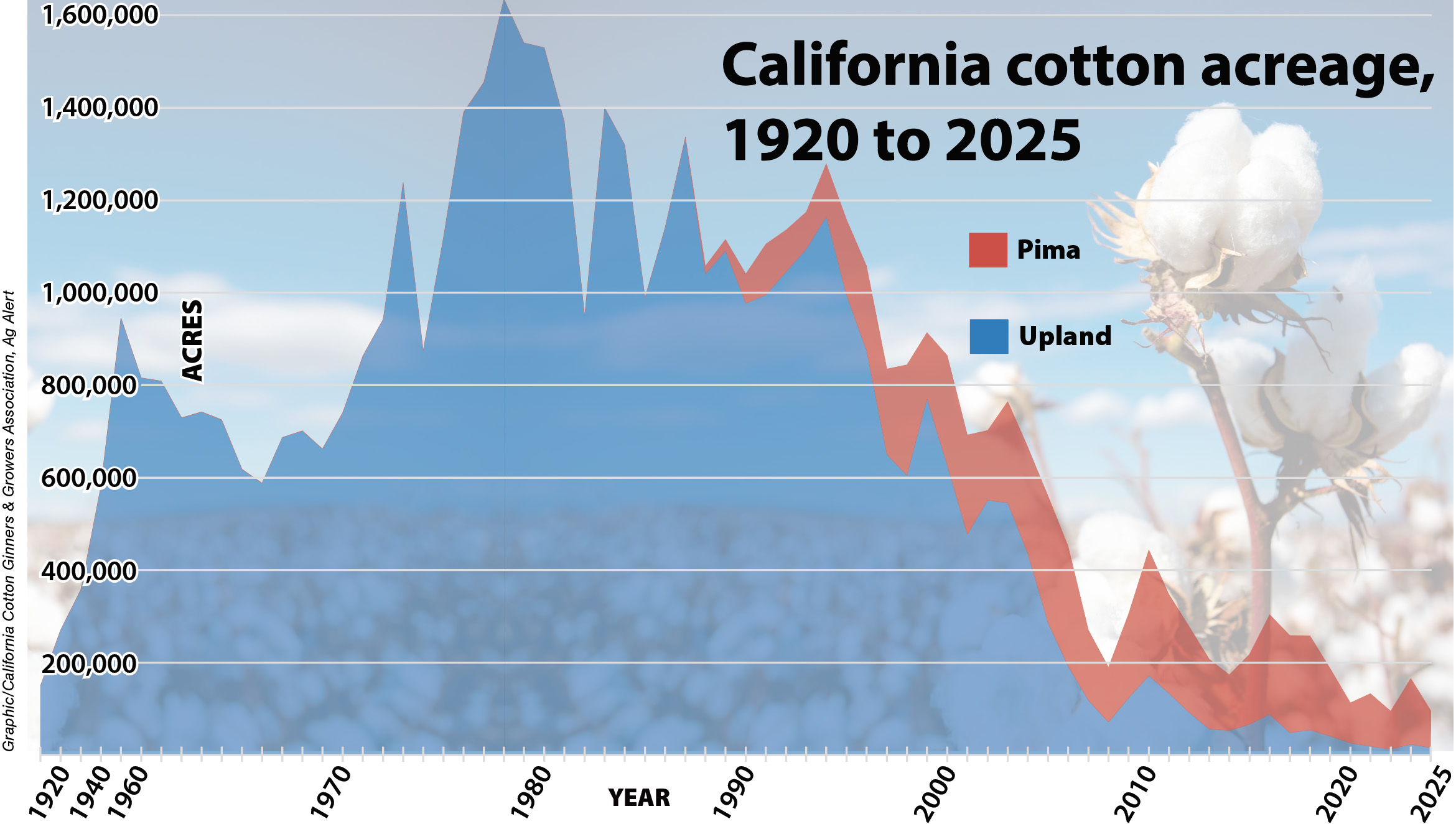

A harvester is in place at a Merced County cotton field to continue picking the 2025 pima cotton crop. California farmers planted 91,000 acres of pima and nearly 16,000 acres of upland cotton this year—a 33% decline in total cotton acreage from 2024 as the industry faces one of the worst markets in memory, according to the California Cotton Ginners and Growers Association.

Photo/Gino Pedretti III

By Mark Billingsley

Jeff Mancebo spends his Sundays doing the bills for his family farm in the Merced County town of Dos Palos, an NFL game sometimes flickering in the background. This year, Mancebo and hundreds of other cotton farmers in the Golden State are getting pummeled like a slow, aging quarterback under an all-out blitz.

The 68-year-old lifelong cotton farmer said his production of harvested Hazera and pima cotton will match low global demand. With cotton prices around the world continuing to stagnate, Mancebo said he planted fewer acres of cotton than he did in 2024, while his grain, almonds and pistachios keep his farm afloat.

“I’m a pretty conservative guy,” Mancebo said. “Cotton used to keep the tree business going, and now it’s the reverse. When there’s a good cotton year, I don’t go out and buy a bunch of stuff. I just roll with it.”

Mancebo said he planted 550 acres of Hazera and pima this year, down from his normal 800-900 acres. He said prices of pima cotton—a premium variety usually much sought after for higher-end clothing, sheets and towels—need to be more than $2 a pound for farmers to break even. But prices have hovered between $1.25 and $1.50 a pound in 2024 and 2025. So, he planted fewer acres than before and now sits at the dinner table paying bills that have become tougher to cover.

Mancebo is not alone.

Roger Isom, CEO of the California Cotton Ginners and Growers Association, said cotton farmers face one of the worst markets in memory. In terms of acres planted and low demand, he said 2025 will be the second or third worst year on record since the CCGGA was founded in 1920.

“We (California) produce 90% of the nation’s pima cotton, and prices are stagnant,” Isom said. “Upland cotton is at 85 to 90 cents a pound right now. That’s the same darn price as when I started 30 years ago. It’s tough out there for our farmers.”

Isom said California cotton farmers produce 600,000 bales in an average year, but that production will drop to an estimated 400,000 bales in 2025.

California farmers planted 91,000 acres of pima and 15,968 acres of upland cotton this year—a 38% drop in pima but a 30% increase in upland from 2024, the CCGGA reported. Overall, cotton acreage declined 33% from last year, the CCGGA said. Kings County continues to lead in plantings, with 47,753 of the state’s 106,968 acres.

Isom said the CCGGA has been on the front lines in the battle over California water restrictions. He also serves as CEO of the Western Agricultural Processors Association and president of the Agricultural Energy Consumers Association, focusing on legislative and regulatory efforts in Sacramento—particularly those affecting water flowing through the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

“We always want to protect as many of the water rights as we can,” Isom said, “because that means healthy soil for all of our farmers.”

Merced County farmer Mancebo said he has an advantage over many of the cotton growers outside his Dos Palos farming region: The Central California Irrigation District in which he farms has a variety of water rights that were grandfathered in almost a century ago.

Mancebo said he pays a lot less for an acre-foot of water than farmers outside the CCID. He said he pays a Tier 1 price of $18 an acre-foot, which also covers water to irrigate his almond and pistachio trees, which are approximately in the middle of their productive lives.

“Water is not much of a worry for us under these normal conditions,” Mancebo said. “But fertilizer, labor and fuel are so much higher that there’s just no way we could plant upland (cotton) and get way less than a dollar a pound.

“We had a good, clean pima harvest last year with about 85% at Grade 1 (best),” he continued. “What I’ve been hearing from the gin manager is the cotton has been great this year, so I expect the same results or better this year. Quality is great, but the demand is down.”

According to Denver-based CoBank, a cooperative bank serving farming-related industries, cotton prices remain depressed despite a smaller U.S. crop.

According to Denver-based CoBank, a cooperative bank serving farming-related industries, cotton prices remain depressed despite a smaller U.S. crop.

The bank said a slowing global economy continues to affect clothing and apparel sales, pushing cotton prices lower. Cumulative U.S. export commitments of upland cotton were down 18% year-over-year as of mid-September, CoBank reported—a concern for U.S. cotton farmers, as 80% of the cotton crop is typically exported.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated the 2025-26 cotton crop at 13.22 million 480-pound bales, down 8% from the previous harvest.

Isom said the stagnant-at-best cotton market has also hurt the revenue streams of businesses that support farmers, such as trucking companies and cotton gins. For example, Fresno County was the top cotton-producing county in the United States 20 years ago and had 26 gins in operation to handle the harvest. Now, he said, Fresno County is not even in the top 150 cotton-producing counties and has just one gin.

“Ten thousand jobs just went away,” Isom said.

Mark Billingsley is a reporter in Carmichael. He can be reached at agalert@cfbf.com.

See related news stories...

• Slow market for cotton leads to drop in planted acres

• Byproducts remain crucial part of state dairy cow feed

• From the Fields: Gino Pedretti III, Merced County farmer