Senate urged to pass farm workforce bill

Farm groups and farmworker advocates traveled to Washington, D.C., this month to urge Congress to pass legislation that would provide a path to legal status for undocumented farmworkers and reform the H-2A temporary worker program.

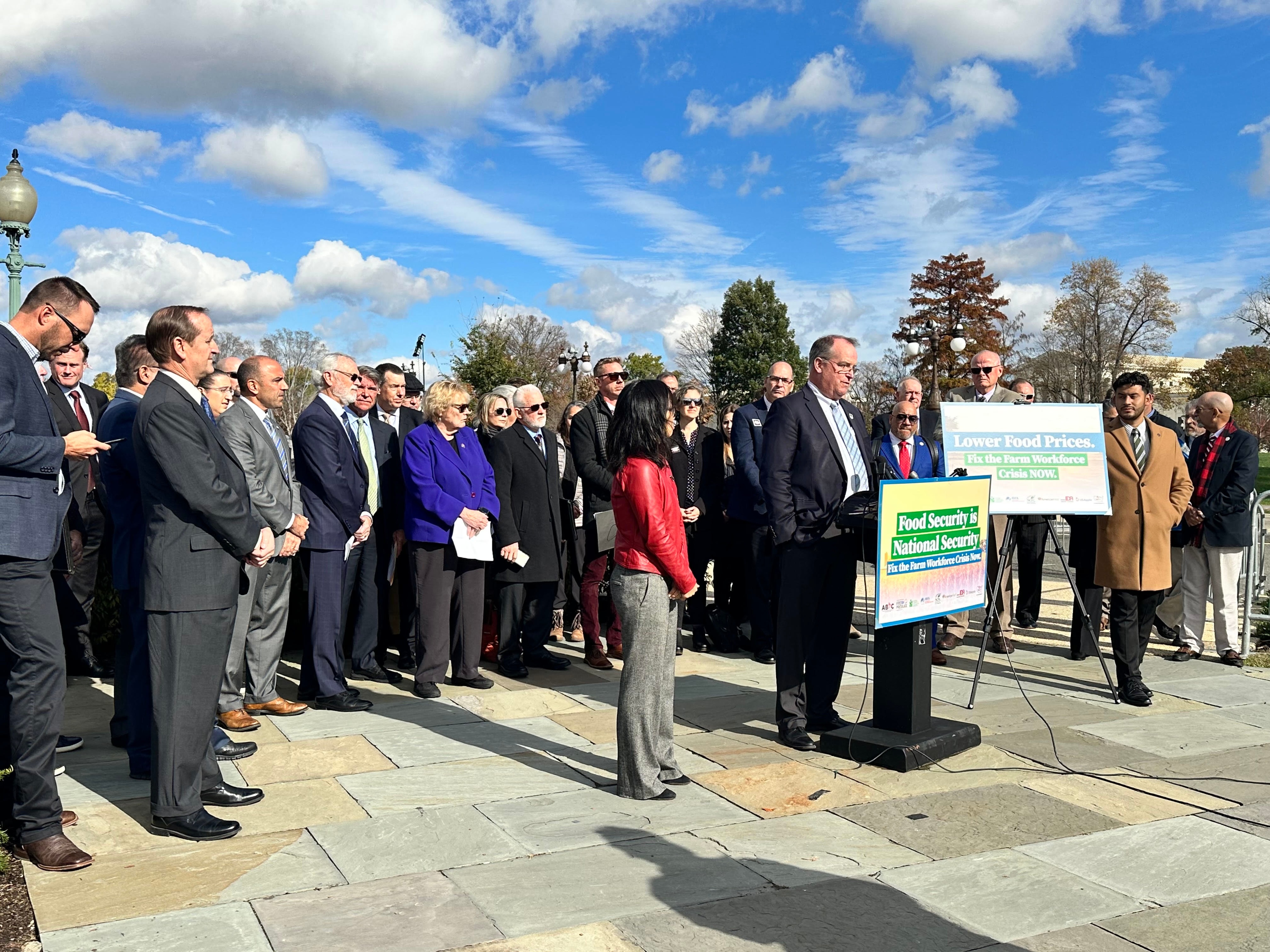

California Farm Bureau President Jamie Johansson speaks outside the U.S. Capitol, urging the Senate to take up and pass the Farm Workforce Modernization Act. Agriculture groups say the legislation, approved in the House, will help protect essential workers for U.S. farmers.

By Caleb Hampton

Farm groups and farmworker advocates traveled to Washington, D.C., this month to urge Congress to pass legislation that would provide a path to legal status for undocumented farmworkers and reform the H-2A temporary worker program.

In March 2021, the Farm Workforce Modernization Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives with bipartisan support. Since then, it has stalled in the Senate. Farmers and other supporters of the labor reforms are pushing Congress to move the legislation forward during the lame-duck session before Republicans take control of the House in January.

California Farm Bureau President Jamie Johansson, speaking at a Nov. 16 event with lawmakers at the Capitol, emphasized the labor challenges many farmers face. “Lack of stability, certainty and affordability are problems Congress can no longer choose to ignore if they wish to keep farming here in the United States,” Johansson said at the event, which was organized by the American Business Immigration Coalition. “We must fix the farm workforce crisis.”

In recent Farm Bureau surveys, roughly half of California farmers and ranchers said they are unable to hire all the employees they need. The worker shortage has driven up input costs and contributed to increased food prices for consumers. Some growers have reported crops rotting in fields because they couldn’t get them harvested.

With few native-born Americans seeking farm work, farmers in California and across the country have for decades employed a largely foreign-born workforce, including undocumented immigrants and seasonal H-2A workers who come to the U.S. on temporary visas, as well as immigrants under various legal statuses.

The visa program, which serves as a stopgap when there aren’t enough local workers, is expensive for farmers, and undocumented workers’ lack of status presents daily challenges and exposes them and their employers to legal jeopardy.

“We have a house that’s built on a sand dune,” said Bryan Little, director of labor affairs at the California Farm Bureau and chief operating officer of the Farm Employers Labor Service. “We’re dependent on a large workforce that is not legally eligible to work in the United States.”

The Farm Workforce Modernization Act would create a “certified agricultural worker” status, authorizing farmworkers to live and work in the U.S. and to come and go from the country. Foreign-born farmworkers lacking legal status, or with a temporary humanitarian status, who performed at least 180 days of agricultural labor during a two-year period preceding passage of the legislation, could apply for the certified-worker status, which would be valid for five-and-a-half years and could be extended.

Applicants would be shielded from deportation and allowed to work while awaiting a determination on their status, which could also confer a dependent status to their spouses and children. Eventually, long-term certified farmworkers and their families may earn permanent residency, or green cards, after meeting certain requirements, including paying a $1,000 fine and working in agriculture for an additional four to eight years, depending on how long they have already worked in the sector.

“This is not amnesty,” Johansson, the California Farm Bureau president, wrote in an article supporting the legislation. “It’s a fair solution for the existing agricultural workforce and their immediate families.” According to some estimates, close to half a million California farmworkers could gain legal status under the act.

“It’s clearly in our interest,” said Little, the California Farm Bureau director of labor affairs. “I think our members are also convinced it’s the right thing to do,” he added, “as an investment in this community of people who have so heavily invested in agriculture over the last hundred years.”

Most undocumented immigrants have lived in the U.S. for over a decade, with the average unauthorized farmworker having worked for their current employer for seven years, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “They’re rooted and settled,” Little said. But they can’t legally work, vote, receive unemployment benefits and often encounter obstacles trying to open bank accounts, access medical care and navigate other aspects of daily life.

“They do what very few Americans want to do or are willing to do,” said Rep. Jimmy Panetta, D-Salinas. “That’s been a cornerstone of our country’s agricultural production.”

But the U.S. population of undocumented farmworkers is aging and shrinking—largely due to improved opportunities for young people in Mexico—leaving American farmers to increasingly rely on labor-saving farming technology and on the H-2A program. This year, there are roughly 35,000 H-2A workers in California, more than 10 times the number of temporary farmworkers in the state a decade ago.

Farmers are not using the program out of convenience. They can only hire H-2A workers if they’ve shown they were unable to find enough domestic workers.

To use the program, they must navigate a slow and burdensome bureaucracy, and pay the workers a higher minimum wage, called the “adverse effect wage rate,” which was designed to keep foreign workers from displacing domestic ones. Farmers also pay for H-2A workers’ travel to the U.S., accommodation, food and transportation to and from work.

“It would be the last thing you would do to try to find workers if you had any reasonable alternative,” Little said.

The Farm Workforce Modernization Act would establish an electronic platform to streamline the filing process for H-2A petitions, expand the program and make it more affordable. It would open it up to dairy farmers and farmers of other nonseasonal commodities, allowing H-2A workers in those industries to stay in the U.S. year-round, and would permit all H-2A workers to change jobs without leaving the country.

The legislation would also freeze the adverse effect wage rate for the next year—and limit rate increases over the next decade—to reign in mounting labor costs. “These are the basic things we’ve been advocating for, for a very long time,” Little said.

The legislation, a compromise with support from growers, farmworkers, Democrats and some Republicans, would also establish an electronic verification system, modeled on E-Verify, and require agricultural employers to confirm their workers are authorized to work in the U.S.

Over the past couple weeks, farm groups visited more than 70 Senate offices, urging them to introduce a version of the bill for the Senate and pass it. After pushing for farm labor immigration reform for years, farm group leaders see the next few weeks as Congress’ final opportunity in the foreseeable future to find a legislative solution.

“We have spent decades on an issue that needs to be resolved now,” Johansson said.

(Caleb Hampton is an assistant editor of Ag Alert. He may be contacted at champton@cfbf.com.)