Early sprinkler designs influence modern irrigation

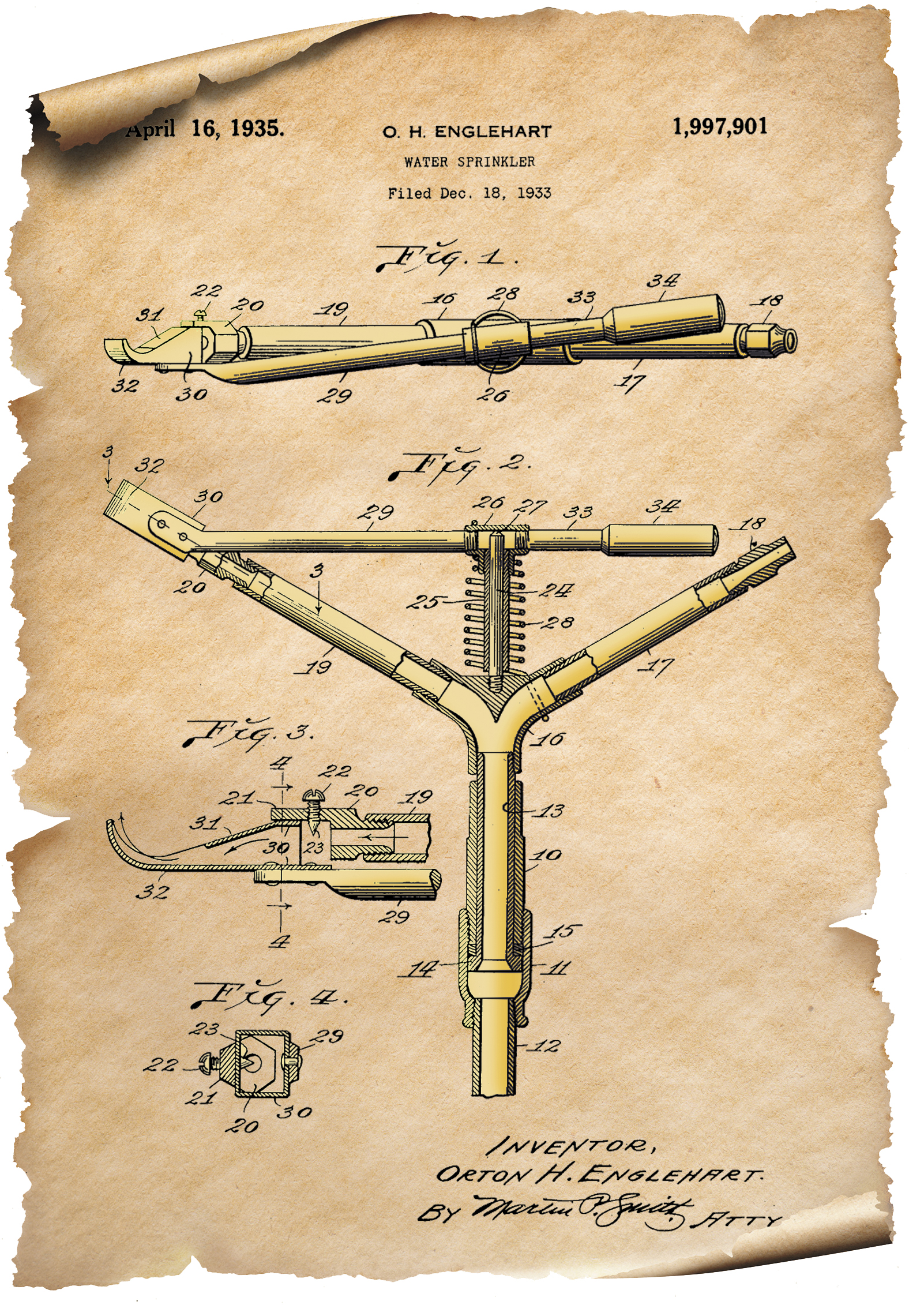

Modern sprinklers continue to build on the innovative impact sprinkler design developed by Orton Englehart for Rain Bird in the 1930s. Rain Bird has since evolved into a global leader in efficient irrigation solutions.

Photo/Rain Bird

By Charles Burt

Agricultural sprinklers used by farmers to irrigate trees, vines and field crops are commonplace in California today.

While these sprinklers are still rare in some parts of the world, variations of early sprinkler designs have been around for many decades.

The first stationary lawn sprinkler heads were patented in 1871 by Joseph Lessler of Buffalo, New York. In 1894, Charles Skinner of Ohio patented the “Skinner” system, which was a variation of the oscillating sprinklers hooked onto a hose for lawns we can buy today.

By 1930, there were numerous sprinkler configurations. Most notable and influential on modern irrigation is the invention of the horizontal impact arm sprinkler by Orton Englehart, a citrus farmer in Glendora. He had an inventor’s aptitude and saw the potential for an improved sprinkler design.

Englehart’s contributions were noted in “Water and the Land,” a 1993 book by Robert Morgan, who explained that during the Great Depression, the citrus farmer gathered as many variations of sprinklers as he could and then took them apart and analyzed them in his shop.

Englehart’s first prototype of an impact sprinkler was completed in 1932, and his neighbor and friend Clement La Fetra encouraged him to apply for a U.S. patent. The two neighbors began producing two sprinklers per day. La Fetra and his wife, Mary Elizabeth, bought the rights to the 1935 patent, giving royalties to Englehart, and Rain Bird was founded.

Graphic/Rain Bird/Ag Alert

The 1935 patent incorporated a variety of features for improved performance. It included concentrating the flow into one large stream, plus one smaller stream and simultaneously reducing the rotation time to less than half a minute. With this feature, Englehart was able to achieve a much greater trajectory radius compared to a spinner sprinkler with the same flow rate. The larger radius reduced the application rate by four times, which is important for California soils with notoriously low infiltration rates.

The design also improved on previous “impact arms” with a better spring and spoon design on the end of the arm that periodically hit the side of the nozzle. This impact action accomplished two things: The impact energy caused the sprinkler to rotate some distance every time the arm hit, and the water jet was temporarily dispersed, causing some of the flow to be applied closer to the sprinkler head.

The spring tension and impact arm configuration and weight, combined with the sprinkler bearing friction, dictate how fast a sprinkler nozzle will rotate. Too fast of a rotation reduces the throw distance, and too slow increases the amount of time the water jet hits a single soil location and therefore increases runoff. If the nozzle jerks too far when the arm impacts, the uniformity of water application can be reduced. An adjustable pin in the nozzle was also included to spread out the water leaving the nozzle. This gave the user the ability to reduce the water jet throw distance and adjust the application pattern, a feature still found in some landscape sprinklers today.

Impact sprinklers were rapidly adopted in California in the late 1930s. In 1942, Jerald Emmet Christiansen of the University of California, Berkeley, published “Irrigation by Sprinkling.” The bulletin discussed state-of-the-art sprinklers and evaluated 19 different impact sprinklers with typical flow rates of 8 to 20

gallons per minute, or GPM, compared to today’s sprinkler flow rates of 2.5 to 5.0 GPM. Christiansen’s landmark contribution is the development of his uniformity coefficient to quantify the overlap uniformity between four adjacent sprinklers.

Always thinking about efficiency, Englehart also developed an idea and received a patent for a part-circle impact sprinkler in 1941. The part-circle option was used to keep water inside field boundaries. You can see much of Englehart’s technology, albeit refined, in today’s brass designs.

He also realized that for uniformity across the entire field, both overlap uniformity and pressure uniformity of the sprinklers should be considered. If all sprinklers throughout a field can operate at about the same flow rate and at the correct pressure for the best overlap uniformity, the field-level distribution uniformity would be improved. These goals are seen in his 1945 remarkable-for-its time patent of an impact sprinkler with a built-in pressure regulator.

As the irrigation industry learned more about uniformity and application rates, and as new materials became available, there have been continuous advancements. Today’s agricultural sprinklers can look completely different from Englehart’s but employ similiar technology. Manufacturers strive to improve the characteristics that were embedded in the original 1935 patent by Englehart—a large, wetted area, smooth and relatively slow rotation, good overlap uniformity and durability.

In 1990, the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers recognized Englehart’s horizontal impact arm sprinkler as a historic landmark for its significance in the field of agricultural engineering.

Charles Burt is irrigation professor emeritus of Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, and founder of the Irrigation Training and Research Center. He can be reached at charlesmburt@gmail.com.